Acute

Pain

Acute pain typically arises suddenly and serves as a warning of disease or a threat to the body. It can be caused by surgery, broken bones, cuts or burns, and usually resolves within 6 months when there is no longer the underlying cause.

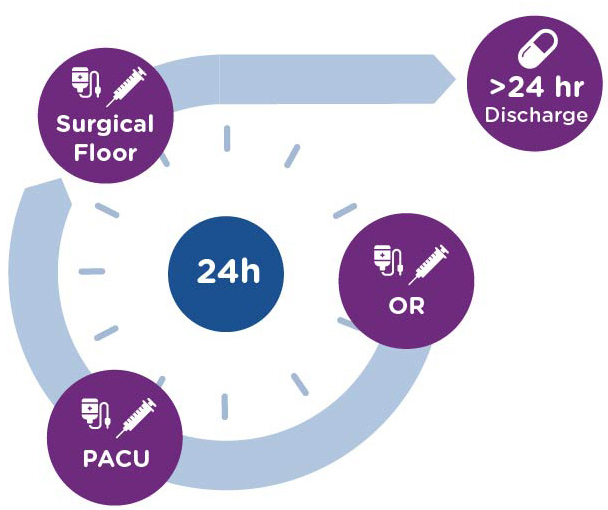

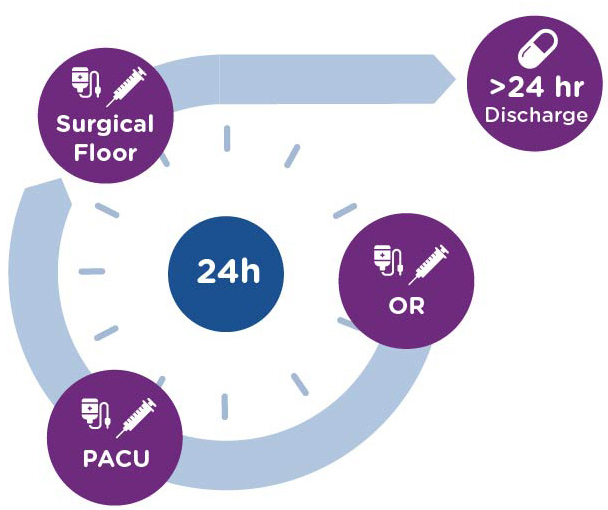

Surgery is one of the most common causes of acute pain. Approximately 51 million surgical inpatient procedures are performed each year in the U.S.1 Postoperative pain is the biggest concern for patients going into surgery, with approximately 86% of surgical patients reporting postoperative pain and 75% reporting it to be extreme or moderate in severity in the immediate postoperative period2.

The Unmet Need in Postoperative Pain

Injectable opioids are a mainstay of treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe pain in the immediate postoperative period, followed by oral opioids in hospital and at discharge. This is despite the frequently reported opioid-induced side effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation and somnolence, the potential for life-threatening respiratory depression, and the risk of misuse, abuse and diversion.

Short-term use of opioids for postoperative pain has been shown to lead to persistent opioid use in ~6% of patients3. This is problematic as the risk of opioid use disorder (defined as a pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress) increases with duration of opioid treatment4. Further, 42-71% of opioid pills prescribed post-operatively remain in the community unused, leaving them available to be diverted for non-medical use and contribute to opioid-related injuries and deaths5.

Ketorolac is a non-opioid, non-scheduled analgesic that has been shown to deliver opioid level analgesia6,7, without the issues associated with opioids. Current injectable ketorolac products are only available in bolus forms (intravenous/intramuscular) intended to be administered every 6 hours, which may result in initial overexposure with safety related risks for patients followed by inadequate analgesia at the end of the dosing period–issues which may be exacerbated if doses are not administered in a timely fashion. If patients do experience analgesic gaps, opioids may be required for additional analgesia, with all the related opioid risks.

- Opioid-induced side effects

- Risk of addiction, misuse and abuse and diversion

- Increased length of hospital stay

- Administrative burdens and liability from opioid stewardship

The Unmet Need in Postoperative Pain

Injectable opioids are a mainstay of treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe pain in the immediate postoperative period, followed by oral opioids in hospital and at discharge. This is despite the frequently reported opioid-induced side effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation and somnolence, the potential for life-threatening respiratory depression, and the risk of misuse, abuse and diversion.

- Opioid-induced side effects

- Risk of addiction, misuse and abuse and diversion

- Increased length of hospital stay

- Administrative burdens and liability from opioid stewardship

Short-term use of opioids for postoperative pain has been shown to lead to persistent opioid use in ~6% of patients3. This is problematic as the risk of opioid use disorder (defined as a pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress) increases with duration of opioid treatment4. Further, 42-71% of opioid pills prescribed post-operatively remain in the community unused, leaving them available to be diverted for non-medical use and contribute to opioid-related injuries and deaths5.

Ketorolac is a non-opioid, non-scheduled analgesic that has been shown to deliver opioid level analgesia6,7, without the issues associated with opioids. Current injectable ketorolac products are only available in bolus forms (intravenous/intramuscular) intended to be administered every 6 hours, which may result in initial overexposure with safety related risks for patients followed by inadequate analgesia at the end of the dosing period–issues which may be exacerbated if doses are not administered in a timely fashion. If patients do experience analgesic gaps, opioids may be required for additional analgesia, with all the related opioid risks.

In the postoperative setting, new, injectable, non-opioid analgesics are needed that provide opioid-level analgesia but are non-addictive and non-scheduled, and reduce the number of patients requiring opioids at discharge.

- Hah JM et al. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1733–1740

- Gan TJ et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149-160

- Brummet CM et al. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504

- Edlund MJ et al. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):557–564. doi:10.1097/

- Bicket MC et al. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11)1066-1071. doi 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831

- Brown CR et al. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10(6 Pt 2):116S-l21S

- O’Hara DA et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;41:556-61